In this episode Romina Achatz interviews Rome based art critic and political theorist Ilari Valbonesi. She talks about her personal journey from Philosophy, Phenomenology, to a practice of inter-being with artists which resulted in an own art radioshow during the Biennale, to writing and curating spaces for artists in Zagreb, Rome, Sarajewo and Vienna.

In an ongoing dialog with Alessio Fransoni she developed and is still developing and weaving a political theory of art. For „Fem Poem“ Ilari Valbonesi is reading texts from her essay „the paradigma of listening“ and her latest work.

Text by Ilari Valbonesi:

Roma, 15 luglio 2024

Sometimes one wonders why a reference is made. One should rather ask how a reference is born, how it crystallises and what crystallises around it. A reference is usually born by chance, thanks to an encounter that is usually accidental, unforeseen. An art criticism or a theory of form that does not start from the works themselves would be a very strange, empty, abstract kind of writing, perhaps to be applied a posteriori with some success.

An art criticism or a theory of form can only start from the works themselves, from the encounter with the works. But which works? If they were chosen a priori, it would be a trick. They would in fact be chosen on the basis of a theory. Such a choice would therefore correspond to what was said earlier, namely the formula of „theory to be applied“. But this is not the case with criticism and theories of quality. They start from the work of art that one simply encounters. And from this, they can gradually establish a familiarity or a series of distances. Or rather, and I really mean the best critiques and theories, one derives from the work a perspective that can – yes – be applied to other works. Not to establish relationships this time, but to make a leap into abstraction and arrive at a purely theoretical level. This means no longer identifying affinities at the level of phenomena, but paradigms that change the way we see and judge everything.

In this interview, I have tried to narrate a curatorial practice through paradigms. Starting with listening.

For several years now, I have been pursuing an “estranged” agenda, which I have exhibited in multimedia projects, radio practices, writings and exhibitions (recently, from The Smile of the Sphynx in 2020 to the Devotion Salon series in 2014, both in progress), and which revolves around a fundamental question. Where is the possibility for an object (a thing) to influence a context? Where is the possibility for an object (a thing) to trigger the discursive and emancipatory formation that is art judgement? A timeless question, because it is at the heart of a discursive formation that is political rather than aesthetic. I am more concerned with a constant examination of the possibilities of the thing, or the thing that is the work of art, to modify the movements of people in a context by virtue of an intrinsic virtue. An intrinsic virtue: which therefore does not escape the consistency of the work as a thing and the materiality of its support.

The means I use to pursue this question are very simple. Firstly, I do not take into account the social hierarchy of places. It is not about proposing alternative spaces. The alternative is always an alternative to something, and that something is the institution. So the alternative is simply the other face of the institution. It seems to me a trap that I have never fallen into, and in fact in my history I have always accepted the space of the institution or the commercial space indifferently. So it is simply a matter of being indifferent to the place, because the place is not the point. The point is precisely the work: in order to prove whether the work, the thing, is capable of determining a conflict, a gap in the trajectories, of appearing as a difference, of activating the place as a difference, its movement must in itself be indifferent to the social positioning of the place. It will certainly not be indifferent to the political positioning of the place. But this is another point, and in order to understand it we need to highlight this apparent paradox: political space is made, and thus ‚positioned‘, by the presence of works, things, people, understood as plurality, and their interactions. It is only in indifference to place that works can be freed from the temptations of the individual experience of the exceptional, of dual hermeneutics, of the „one-to-one“ relationship, and show us that they are irreducibly third among themselves and third among us. The point, then, is the work. As Alessio Fransoni admirably writes in his Political Theory of Art (p.33): „

The work of art enters the world as a new beginning among other beginnings and forces others to move, to take a position, to judge, in other words, to act. In this sense, it is in turn liberating. Such irruption also resembles a birth: it is not a controlled process, but a partially blind act that triggers unpredictable effects. „. And this is the second simple element of the programme: the selection of the works, not the artists. The artist, his name, his signature, are already in the context, the value, the society. But from a political point of view, it is not the artist, but the works. So do not be offended if I put the works in their place. The works are charged with the burden of presence, they have to prove in the field whether or not they are able to differentiate, to make a difference. Whether they are capable of exercising a certain agency or not. The political enigma of art lies in this ‚however‘, an unguaranteed ‚however‘ that manifests itself with the force of fact. And that is why I suggest you read Alessio Fransoni’s book “Political Theory of Art”, just published by Academia Verlag, which I had the privilege of “listening” and read through its long development and gestation.

The Black Paradigm.

In 1985, Frank Stella published a short essay on Caravaggio in the New York Times Magazine, the content of which had been the subject of a lecture given at Harvard as part of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures. For Stella, Caravaggio has a place of honour, and the reason for this lies in a comment on the relationship between painting and the environment: „He is able to take the pictorial space he creates in his own studio and move it into a public space without making any concessions to the structure of that space. Even now, his paintings create and occupy a specific, self-contained space‘. I think the key to pictorial space and the aforementioned independence of the painting from its environment is Caravaggio’s blackness. This is in fact something surprising and unprecedented. It is not a background in the sense of a figurative motif, nor is it a simple illusion of a dark environment. The figures move into it and occupy it. It is not simply an empty space in shadow. It is the very degradation of light into shadow, a depth explored by the very force of painting, without architecture, without form itself, without signs. Black is the absorption of all colour, it is the rest of form, that to which form returns, Caravaggio’s black as black absorbs all colour, it attracts it, but it does so slowly, so much so that in this slowing down space and movement are perceived. Caravaggio’s black is there, made of paint, to radically question the emergence of something in the light, of emergence in art in general, and thus the relationship between pictorial space and support: plastic space in painting. It is the discovery of blackness as a paradigm of withdrawal by leaving space, of the emergence of something without that something being completely free of that from which it emerges. For it is from this black that the form emerges and in this black that the form rests, and it is in this double movement that the work finds its unity. What is this blackness? It is background that is not background, it is that from which form emerges and in which it rests. It is the paradigm. But not to establish affinities and aggregate other works. But to look at other works, all works, with different eyes.

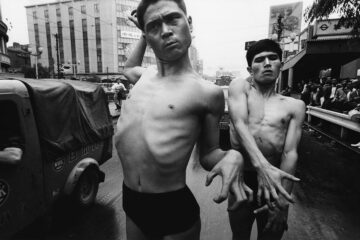

The last expedient in the programme is movement. The movement of the work is understood. Already in the Devotion Salons, I experienced the continuous rearrangement over the course of the exhibition. Otherwise the exhibition runs the risk of becoming in turn context, scenography. And I have also experienced, at times, the changing of the artists represented in the exhibition. For how could the agency of the works ever be experienced if we did not allow them to move in space? And also to add or change themselves. How could we ever make the political effective if we were not invited to a continuous change of perspective?

Die Schwarze welle

Thank you, dear Romina, for our interview that calls for the possibility of responsive listening (and writing). And thank you, dear artists, for your incredible artworks that accompanied first studio exhibition at Brauhausgasse 31: the occasion of a fortunate and at the same time virtuous encounter. Towards a Neue Plastik Welle.

(to be continued)

@ilarzip